Today a group of people sat down in Providence to talk with Senator Whitehouse about his bill to create a federal parole system.

Today a group of people sat down in Providence to talk with Senator Whitehouse about his bill to create a federal parole system.

The bill is hailed as a “prison reform bill,” and passed the Senate Judiciary Committee; a clear indication of the shifting tide on political ideology over the past few years. This ebbing of the ‘Tough on Crime’ rhetoric includes many people who were bipartisan architects of the prison industry itself, and jibes with Attorney General Eric Holder’s public desire to make the system “more just.” Of course, this indicates he believes it is currently less just than it should be. The voices you have heard over the past several years talking “reform” are the result of those of us who have been peeing in the pool long enough to warm it up so everybody can get in. Even if just a toe, they’re getting in.

This prison reform bill is quite overstated however, and falls well short of what the public is truly calling for- something Senator Whitehouse appeared to be going for with his former bill to create a commission of experts that would propose a national overhaul.

This prison reform bill is quite overstated however, and falls well short of what the public is truly calling for- something Senator Whitehouse appeared to be going for with his former bill to create a commission of experts that would propose a national overhaul.

The Recidivism Reduction and Public Safety Act of 2014 will have no impact on state prisoners, where six times more men, women and children are serving prison terms than under federal law. Furthermore, it will have no impact on the 722,000 people currently sitting in a local jail- a snapshot of the 12 million who cycle through that system [see the graphic above]. Its not easy for the feds to control state crime and punishment under the law, but like anything else: the feds could put strings attached to all the financial subsidies of a bursting prison industry.

What’s in it for anybody?

The bill will impact tens of thousands of people nationally who will now gain an opportunity at parole, but what the bill now deems “Prerelease Custody.” They can do this by engaging in what we once considered educational and rehabilitative programming, but the bill deems “Recidivism Reduction” programming. This wordsmithing is no different than calling oneself a “Pre-Owned Car Dealer” (which is what they do, these days). To assess the merits, it is important not to be distracted by shiny new things.

The Good Time credits earned by federal inmates are not available to everybody, and they are not time off one’s sentence the way they commonly are applied to state custody. (The time can be converted to parole time). Furthermore, parolees in halfway houses and on electronic monitoring pay for their own incarceration, sometimes to their own financial ruin. Thus, this is not a handout by any means yet does pose a possibility for the prison system to generate additional revenues from the predominantly low-income and struggling families trying to rebuild a life after prison.

Slavery by another name: Prison Labor

The bill prioritizes an expansion of prison labor, viewed as a form of rehabilitation and method of reducing recidivism. It is impossible to discount the value of having a prison job for the prisoner, even at 12 cents per hour of income. However, it is difficult not to think of one ominous phrase “Arbeit Macht Frei” infamously posted over Camp Auschwitz. Work makes you free. A prison worker gets time off their sentence, and this bill calls for the Bureau of Prisons to review in what ways the prison labor force can be used to make goods currently manufactured overseas, so as not to cut into the free labor pool.

The use of prison labor is controversial, to say the least. Some critics have called for a repeal of the 13th Amendment, which provides for slavery of anyone convicted of a crime. This provision allowed for the massive “convict lease labor” that built a considerable amount of American infrastructure after slavery was abolished. The legal framework that is said to have freed Black America also allowed for people to be rounded up and placed, fundamentally, back where, essentially, Black America had been liberated from.

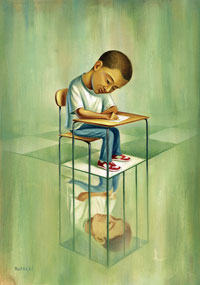

Today, prison labor exploiters capitalize upon incarcerated people’s desire to stay busy rather than sit on a bunk all day. This sort of macro-management does not take into account the relevance of a worker’s feelings. People in the system are treated with the callousness of lab rats, which may be all fine in the punishment phase, yet counterproductive when doing anti-recidivism, rehabilitative, or reentry programming. Does Johnny have a job, a home, or health care? Check. The assessments never ask if Johnny is happy.

Reentry programming still being run by those who have never reentered

The Recidivism Reduction and Public Safety Act also focuses on reviewing current reentry programs and developing federal pilot programs based on the best practices. This is an admirable goal and an obvious step to take. The challenge is to correctly assess best practices, and then implement what might feel controversial. For example, many policies prevent formerly incarcerated people (FIP) from affiliating with one another, and yet this bill references mentorships. It is likely that the drafters visualized a well-intentioned citizen with no criminal involvement and demonstrated success showing the way to someone getting out of prison. Yet such a person has very little to offer in the sense of mentorship. An FIP often grows frustrated with social workers, mentors, and probation officers who feign to understand the pressures of post-prison life. The best mentors are role models, and in this scenario will be FIPs.

This legislation also puts a considerable focus on risk assessment models, as though they are a new pathway to success. However, these tools have been in use for decades, and nowhere in the bill is there a call to study their individual accuracies. Several states, for example, uses the LSI-R scoring system. The irony of in-custody assessments, that take all of forty five minutes to conduct, then a few minutes per year to update, are how a high-risk prisoner can be a low-risk free person. Conformity in prison does not translate to the attributes required for successful living in free society. Furthermore, an antagonistic interviewer will likely invoke anti-social responses from a someone, thus along with their past criminal activity, setting the foundation for an entire course of reentry opportunity.

The fundamental flaw in many prison-related programs, particularly after the Bush Administration’s Second Chance Act, is the lack of involvement of affected people. The Senator’s roundtable consists primarily of law enforcement and some non-profit workers with no conviction history. The stakeholder list is upside down. Law enforcement does not have a stake in my successful reentry. In fact, they have a stake in my failed reentry- so yes, they are a stakeholder, but in a perverse manner. After being punished by a group of people, be it months or decades, there is no trust in place for the punisher to then be the healer. For the government to believe otherwise only underscores these misconceptions and miscommunications of trying to reposition the pawns on the board.

Apparently there were two affected people at the table. Rhode Island is a very small place with few affected policy experts and activists. Curiously, however, none of those were invited- and most were unaware until they saw the Senator’s press release.

It is not for law enforcement, politicians, or nonprofits to decide the leaders, or the participants, from any group. That task is left to those constituencies, be they in a foreign nation, laborers, or families with conviction histories. An American democracy needs to maintain respect for, and support, democratic principles within communities.

The second class citizens

No public defenders, and hardly any nonprofits, are run by people who have “been there, done that.” When efforts like this use those agencies to speak for a disempowered population, it only further delegitimizes people with criminal histories, only furthers the second-class citizenship, and continues to render us without a voice. Rather than confronting any counter-narrative an FIP presents to policy reform, we are often disregarded as unruly, unmanageable, or uncivilized. Yet we are the ones seeing our selves and our family members dropping off the map, figuratively and literally, every day. Reducing recidivism and increasing public safety can only be done by a full restoration of people to being equal and valued members of society, especially the overwhelming number who are (on paper) “citizens” of America.

Efforts like these are akin to watching someone fish without bait. As expensive a boat, pole, and hook they use… they just don’t realize why the fish don’t simply leap onto the hook.

When Candidates Oppose the Right to Vote

Louisiana has approximately 45,000 people living in the community on probation and parole, with 7000 being supervised in New Orleans. These people live in every district, pay taxes, work, raise families, and are denied the most fundamental right of democracy: voting. It is the most basic right of citizenship, as recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court and the United Nations. Those denied the right to vote are essentially “stateless persons” or internally displaced refugees. They, arguably, have fewer rights than a foreign citizen.

None of the candidates appeared overly familiar with the issue, and they presented little analysis or rationale other than the understandable instinct that stripping someone of all their rights is an acceptable punishment for crime. Only one candidate, Ira Thomas, was available to speak with me. After explaining a few basic elements of the situation, he expressed a willingness to work on the issue and truly encourage people to act like, and be, full citizens of the city. He is also the only candidate who has not overseen part of 40 years of failure, corruption, and death at the Orleans Parish Prison.

Most people on probation never went to prison. Most of them committed lesser crimes, or served their time, which is the only way they are able to be out in the community. The judge released them from court with a caveat: stay out of trouble for a while, and you can escape the Sword of Damocles that is suspended over you. Judges and probation officers expect people to hold an honest job or go to school, and live in peace. No judge ever sentenced a person to stop voting, or to be homeless and unemployed.

The Housing Authority of New Orleans (HANO) recently agreed to ease their policy on excluding entire families where one person has a criminal record. This change stemmed from the organizing efforts and technical expertise of Voice of the Ex-Offender (VOTE) and Stand With Dignity. Similarly, Mayor Landrieu has decided to “Ban the Box” for the city, allowing people with criminal histories a realistic chance to apply for a job by holding back those questions until the interview. These moves are a direct response to the nationwide over-criminalization of people during the previous three decades.

People who are encouraged to be part of the community are more likely to abide by the law. People with jobs are less likely to need illegal activity to pay the bills. Ultimately those who are doing the right thing are those who want to show up and cast a vote. But this isn’t even about criminal justice policy, rehabilitation, and reentry. It is about democracy, and more nefariously: about policies crafted to counteract Black Suffrage, and have now created a class of “unworthy” people, no different than the Black, Native American and female people who came before us.

My question for candidates is this: what is their message to me and my 7000 neighbors: Get involved with New Orleans, stay in the shadows, or simply leave?

Bruce Reilly is a law student at Tulane University. He is denied voting rights after moving to Louisiana, although he drafted the constitutional amendment that restored his rights in Rhode Island.

Share this: